“Volya”

In Ukrainian, the word means “will.” Darya Levchenko ’19 MA and her fight to preserve the arts embody that spirit of Ukraine’s people.

Darya Levchenko ’19 MA believes words have revolutionary power. As someone who grew up with Russian and Ukrainian as her first languages, it’s all about what she says and how she says it. A translator and film curator who lives in Kyiv, Ukraine, Darya grew up in Zaporizhzhia, an industrial town in southeast Ukraine, where Russian is the dominant language. After the past two years of seeing Russian occupation of the region near her childhood home and hearing the discordant symphonies of Kyiv’s air-raid alerts, Darya chooses to no longer speak in Russian. “I choose Ukrainian, or English or German or French,” she says. “Anything but Russian.”

Her rejection of the Russian language is part of Darya’s cultural resistance to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Since the February 2022 invasion, she’s helped organize travel and arrange safe havens for refugees fleeing their homeland. She’s translated for organizations getting Ukrainian news stories out to the world to counter Russian propaganda. And Darya, who came to NC State in 2017 on a Fulbright grant to pursue a graduate degree in English with a concentration in film studies, has curated Ukrainian films for festivals in her country and all over the world. The arts are Darya’s battlefield as she works to ensure that Ukraine’s vibrant culture is not a casualty of the war.

That work continues today, even with the everyday reminders that war is always nearby. There’s the Scotch-taped “X” on her window overlooking the city to prevent the glass from shattering into shards should a blast reach her apartment. Candles stand at the ready if power goes out. There’s the crescendo hum of the city’s air-raid sirens, which sometimes interrupt her walks for her two French bulldogs, Cherie and Ema (short for “Emancipation”) and force them to quickly get inside. Amid all that, Darya sees two choices, to flee or attack. While she admits that she’s no front-line fighter, she’s committed to staying in Kyiv to do her part.

“I’m trying to promote what is left of our scattered body of culture,” Darya says, “and I’m trying to build lifelines from abroad to Ukraine.”

I’m trying to promote what is left of our scattered body of culture, and I’m trying to build lifelines from abroad to Ukraine.

“Вторгнення” – INVASION

Darya, 29, was not quite expecting a full-on invasion by Vladimir Putin and Russia in February 2022. She was working for a film festival in Kyiv, set for that March, and looking forward to an April trip to Iceland with Sasha, her boyfriend with whom she lives, and her childhood best friend. In early 2022, she had been hearing reports from her Western friends that an invasion was imminent. But inside Ukraine, President Volodymyr Zelensky had downplayed the threat of Russia charging into the country.

Then came the morning of Feb. 24. Darya and Sasha were awakened by a phone call from his sister in Zaporizhzhia, informing them that Kyiv was being bombed. They walked out onto their apartment’s balcony overlooking central Kyiv and heard the aerial assault. “We saw smoke,” she says, “so we knew it was on.”

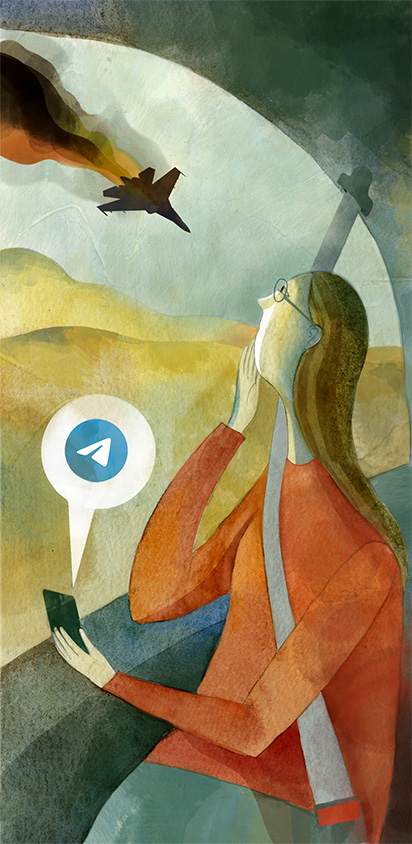

The couple spent the next few hours throwing clothes and food in backpacks and waiting in long ATM lines. They met up with her younger cousin, whom she calls “a brother,” and set out to meet friends in Brovary, a little east of Kyiv. From there, they decided to escape to western Ukraine on a 400-mile trip to Drohobych. With GPS out, Darya relied on Telegram, a messenger app people were using to communicate, to find the safest routes. “You don’t know where the next bomb is going to land,” she says. “We had to choose the road to take, and one of them was where a burning plane was going down, and another one was right next to the airport that was probably going to be targeted, too.”

We had to choose the road to take, and one of them was where a burning plane was going down, and another was right next to the airport that was probably going to be targeted, too.

What should have been an eight-and-a-half-hour trip took three days to make it to Drohobych, where they stayed with a friend’s parents. Darya remembers a moment of paralysis staying in a house outside of Kyiv at the start of the journey, freezing up for 10 minutes and not wanting to get in the shower for fear of not being able to get dressed if a bomb hit while she bathed. She remembers Sasha’s father, a Ukrainian expatriate who had spent the last nine years living in Russia, texting them congratulations for being “liberated.” (It’s a misguided sentiment, Darya says, prevalent among some Russian citizens and sympathizers that Russia was liberating Ukraine from fascists.) And she remembers trying to convince her mother in Zaporizhzhia, close to the fighting in the east, to escape west with her. But her mother is a doctor who immediately went to work caring for injured and sick children. And she also was taking care of Darya’s grandmother, who has Alzheimer’s, so evacuation wasn’t an option. “I wasn’t sure I’m going to see her again,” Darya says, “and there was a lot of heartfelt phone calls, and you’re crying your eyes out because you don’t know. Is it going to be the last conversation?”

“Стійкість”– RESILIENCE

Once settled in Drohobych, Darya began helping others who wanted to evacuate. She took stock of her connections across Europe, finding friends who could welcome anyone she knew wanting exodus. That remains one of the major crises of the conflict in Ukraine, with close to 6.3 million Ukrainians having left everything behind in their home country, according to the latest data from the United Nations.

Darya also geared up to fight what she describes as the Russian propaganda machine coming out of Moscow. A student of languages, she is fluent in English, German, French and Spanish, and can hold her own reading Polish and Italian. She has a college degree in foreign languages and got her first English lessons from bootleg VHS copies of American films overdubbed in Ukrainian. “When I was watching Lion King growing up,” she says, “I could hear the original English language and the original songs.”

So Darya joined up with members of an organization associated with the U.S. Agency for International Development to translate firsthand reports of what was happening on the ground in Ukraine and disseminate them to embassies and news agencies. For instance, when Russia bombed a Mariupol maternity hospital in March 2022, Darya says news stories started appearing featuring a Ukrainian beauty blogger standing in front of the bombed hospital. Russia then denied the validity of the story, claiming the blogger was an actress. Darya and others were translating the transcripts sent by Ukrainian soldiers who were in Mariupol and then got them to the organization that dispersed them to media outlets.

Darya says that any time she translates, it’s “an act of resilience,” something she can do to fill words with power and truth in “different languages so people can read it and have something to counter the giant mass of propaganda Russia pumps out every day.”

“Повернення”– RETURN

Darya and Sasha returned to Kyiv in May 2022. The city felt different. A number of their friends were on the front lines fighting in the east. There were no sounds of children. No cars, which also meant no traffic and pollution. She says for the first time in her city, she could hear the birds and see the stars through a clear night sky. But a jarring sound blared a new reality across Kyiv. “It felt very much unsafe,” she says. “When you hear the air raid every day, you need to know where the nearest shelter is.”

It felt very much unsafe. When you hear the air raid every day, you need to know where the nearest shelter is.

Once back in Kyiv, Darya was ready to jump back into her work as a program coordinator and curator with the Docudays UA International Human Rights Documentary Film Festival, an annual festival based in Kyiv that holds competitions for short and full-length documentaries from around the world about human rights issues. Docudays had canceled its planned festival earlier in March, but by that fall, people started reaching out wanting to find some way to gather to watch movies. So Darya and others with the festival organized an event for a weekend November 2022. They showed films in Kyiv. People came, and Docudays sent the movies out on Zoom for those who couldn’t make it. They even secured a generator in case there was a blackout. All told, 22,000 people attended in person and online.

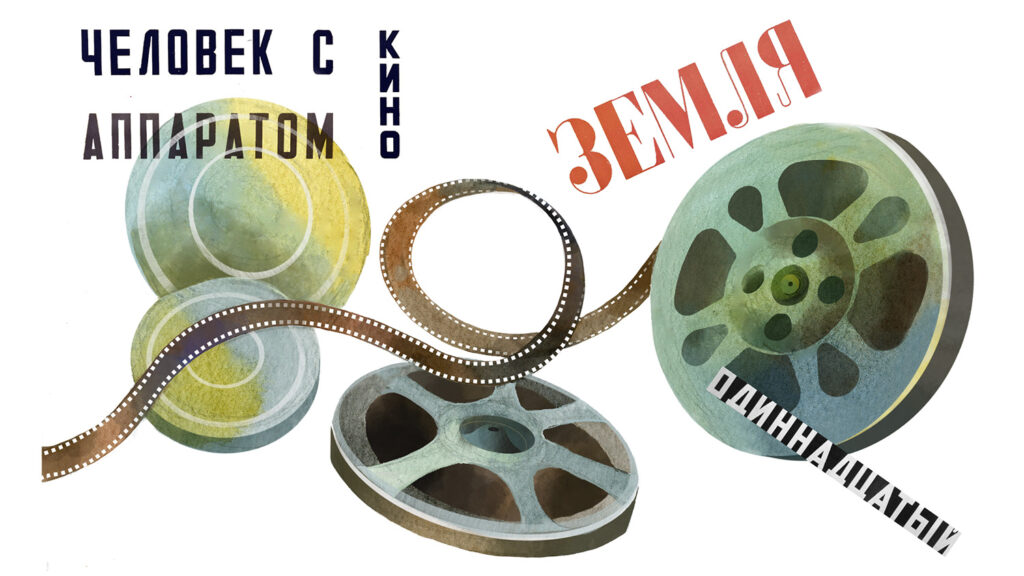

Darya is proud of Ukraine’s rich film history, dating back to the country’s first national film production cooperative in the 1920s. She’s quick with a crash course on Ukrainian directors, citing the documentaries of Dziga Vertov in the 1930s, the poetic vision of Sergei Parajanov, an director of Armenian descent who became a leader in Ukrainian cinema in the 1960s, and the work of Oleksandr Dovzhenko, whom she calls “the biggest name of early Ukrainian film” and whose early silent films are celebrated by international critics today. With that history as a backdrop, it doesn’t surprise Darya that several other film festivals across Ukraine showed movies in the midst of war. She says there were film screenings in cities around Ukraine in ground-level places that were the safest, like schools and metro stations. “People still wanted to get together and feel the community,” she says, “and the war really mobilized Ukrainian society as a group that wants to create something together.”

People still wanted to get together and feel the community, and the war really mobilized Ukrainian society as a group that wants to create something together.

That want went global. AFI Silver Theatre and Cultural Center, where Darya interned during a summer while at NC State, reached out to her for suggestions of Ukrainian titles to feature at a showcase near Washington, D.C., as donations came in there. She worked with a visual arts organization in her hometown of Zaporizhzhia to establish a residency for Ukrainian artists in Germany. She also worked to get an art installation in the city. And she’s currently working on a project that will enable Ukrainian animators to have small residencies in Germany.

All of this falls under her self-assigned job description of “preserving Ukraine’s creative economy” during war. “I’m trying to secure alternate ways for people to hear our stories,” she says, “and also for our film industry to survive because right now, not many films are being made, but the film professionals can show their previous work, get new connections and work on their next projects.”

“ВОЛЯ”– WILL

When Darya speaks about life in Kyiv today, it’s as much a place in her psyche as it is geographical. Constant fear and stress have taken her away from some of the small things she used to enjoy. She grew up an avid reader of science fiction, Ray Bradbury being her favorite American author. “I’m not reading much right now, to be honest,” she says. “Just reading and focusing on something is difficult.”

Then there are the costs of the war. She’s had to get used to the air-raid sirens. When Russia launched 20 rockets on Kyiv in August, Darya and Sasha gathered their dogs and went into their bathroom “to just keep to the rule of two walls.” Darya worries about her uncles, most of whom now serve in the army. One of her friend’s boyfriend was killed in the east at the front lines. An acquaintance she’d just met at an office in Chernihiv was killed in a bombing in August. She searches endlessly for the right words, finally saying, “. . .this idea that something you’ve just experienced, the city you’ve just been to where you had coffee, that same place gets bombed,” before trailing off. She feels that assault on familiarity often. She recently traveled by bus back east to Dnipro, a city near her hometown. The bus station there, which she says has been around since the 1970s, was bombed after she’d been there. “I have a lot of memories going through that bus station, and that was gone.”

In Kyiv, Darya sees shattered windowpanes in high rises. And there’s a blown-out building near the metro station closest to her. If anything good has come out of the last two years, she says, there is a more tangible feeling of togetherness as she walks through the city these days. People around the city seem friendlier to their neighbors now and speak more to one another on the streets. “People have become more reliant on each other,” she says, “more trusting.”

People have become more reliant on each other, more trusting.

She still travels freely throughout Ukraine. She suspects it will take decades to completely rebuild, but she’s already seeing progress. In the northern regions, she says, the bridges, roads and schools have been rebuilt. She still worries about her mother and grandmother in Zaporizhzhia, where bombs have destroyed friends’ and relatives’ homes. She speaks to her mom every day by phone and travels to see her at least every few months. Her mother, who gardens, regularly sends Darya fruits and vegetables. “Because,” Darya says, “tomatoes in the south are so much better.”

Film is still her nine-to-five job as she continues her work for the Docudays festival. She spent the summer curating films for an international film festival in Estonia while continuing her cultural diplomacy work. In August, she helped organize trainings for first responders in psychological resilience. And she’s working on a research paper on how film festivals can be a vehicle to help enable Ukrainian diplomacy.

Darya says the work has kept her going amid a war in her backyard. The constant kinetic energy of translating and curating keeps her in motion. It’s her way of coping. But she also draws strength from something else. She says it’s the same idea that has made the Ukrainian people so resilient.

I like the word ‘volya,’ which roughly means ‘will’ or ‘willpower.’ It also can be translated as ‘freedom.’

It’s the power of a word. Her favorite Ukrainian word. The word is ВОЛЯ. The English pronunciation is “volya.” The word, she says, is coded into the Ukrainian coat of arms. It is Darya’s motivator.

“I like the word ‘volya,’ which roughly means ‘will’ or ‘willpower,’” she says. “It also can be translated as ‘freedom.’”

Darya Levchenko ’19 MA will be on campus for events in January 2024. She will be delivering a talk titled “Programming for Change: Ukrainian Contemporary Cinema in the International Film Festival Circle as an Instrument of Soft Power in Times of Crisis” on Wednesday, Jan. 17 at 3 p.m. in Caldwell Lounge. It is free and open to the public. On Jan. 18 at 6:30 p.m., she will be introducing a series of 10 short animated films by Ukrainian filmmakers for NC State University Libraries’ Global Film Series. Follow the link to register.

What a powerful story and statement of resistance on the part of a creative Ukrainian woman, with NC State connections. Her testimony, her observations about the lived experience of War and her art touch the heart. Thank you NC State magazine for this remarkable story.