Making up for Lost Time

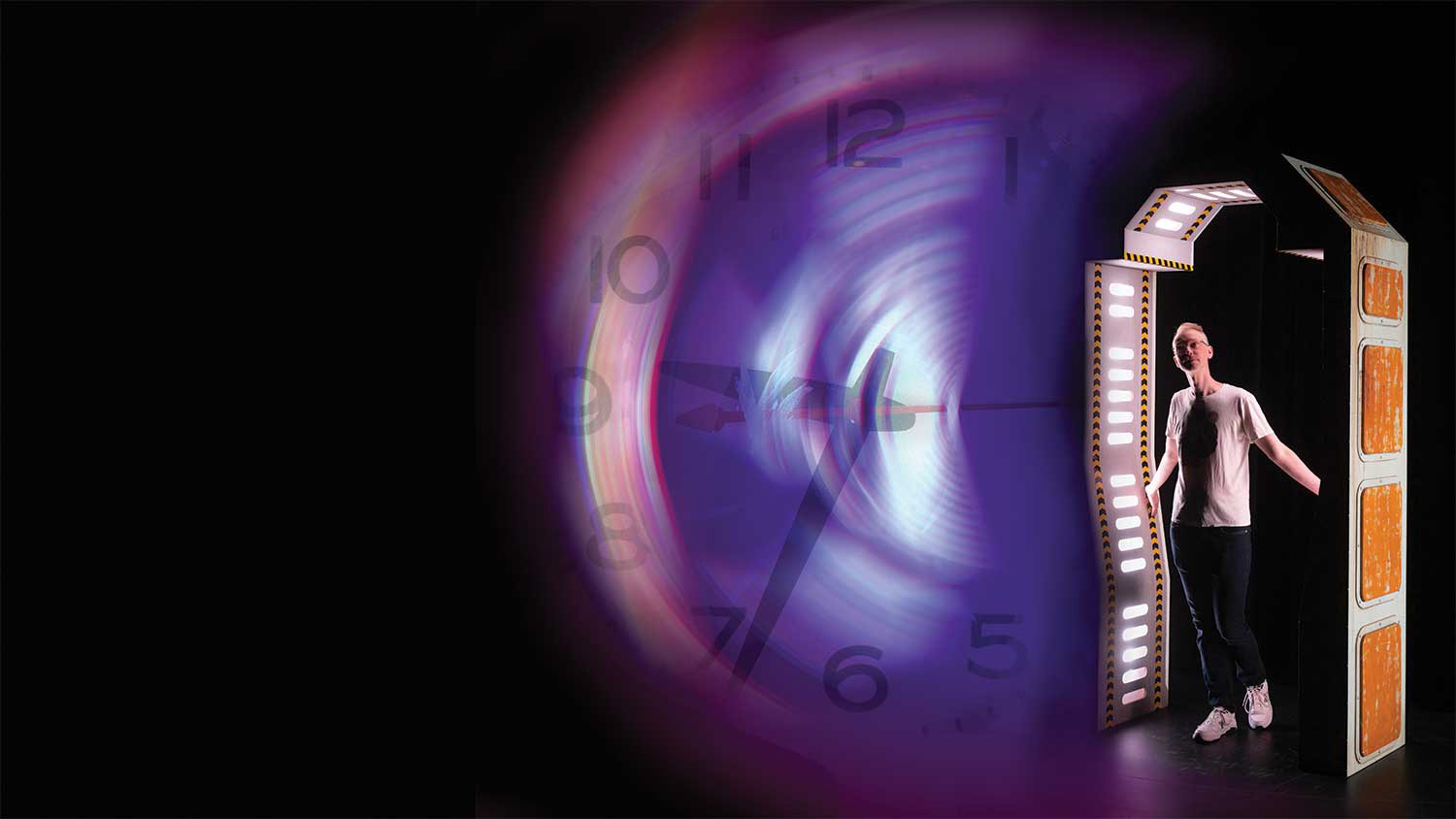

With crime scenes, time travel and an on-campus scavenger hunt, University Theatre staged a mystery while reviving campus amid the pandemic. Photography by Marc Hall ’20 MA, NC State.

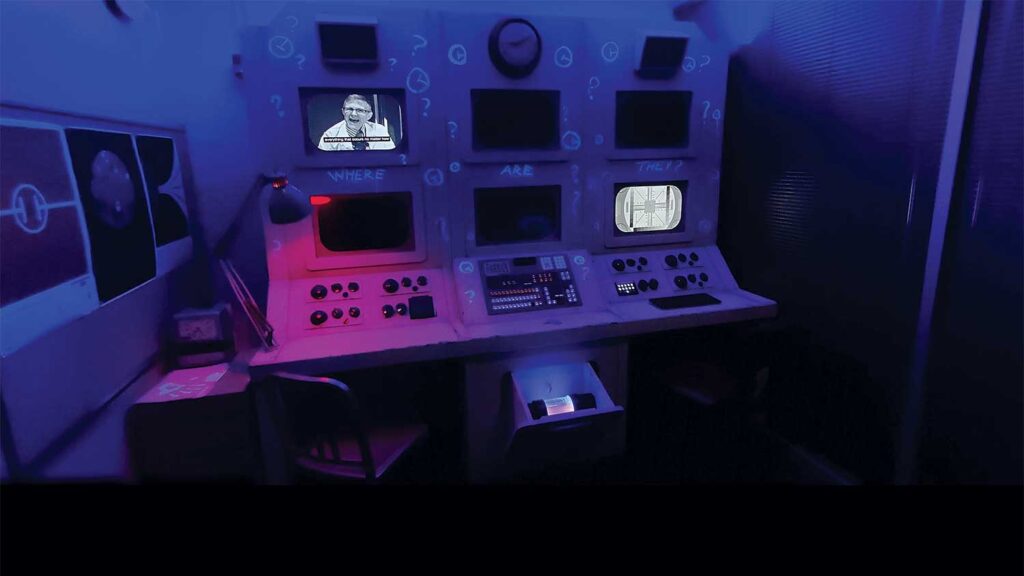

The website looked real, just like an NC State website. “The Institute for Temporal Observation and Application” gave a Broughton Hall address and even included the slogan: “Think and Do . . . the Impossible.” In a grainy welcoming video on the site, the Institute’s founder, Dr. Alistair Beldon, makes an oblique reference to time travel — and invites students to volunteer for a research project.

It all looked so — well, real — that NC State’s Physics Department even had to ask for a disclaimer on the site.

No, NC State was not studying time travel. This was an illusion — an elaborate one that took several hundred participants into a genre-defying theatrical production spread out over several months of the 2022 spring semester. The action took place in multiple locations across campus, immersing participants in a story in which they would help create the outcome. And all along, it was shrouded in secrecy.

The creators — although many participants weren’t aware of it until well into the semester — were the folks at University Theatre. Jayme Mellema, the theater’s resident scenic designer for 10 years, normally spends his time in Thompson Hall creating the scenes and stagecraft that bring a performance to life. When Mellema and his colleagues realized there would be no live theater in the fall of 2020, “We were thinking, ‘What can we do?’ ”

A bit of a science fiction buff, Mellema was working on a script about time travel. An idea took root — a time-travel-themed production with scenes taking place over the course of a semester, where visitors could come in small groups, uncover a series of puzzles and engage with an ongoing story.

It ended up being part scavenger hunt, part escape room, or as Mellema describes it, “a live-action video game.”

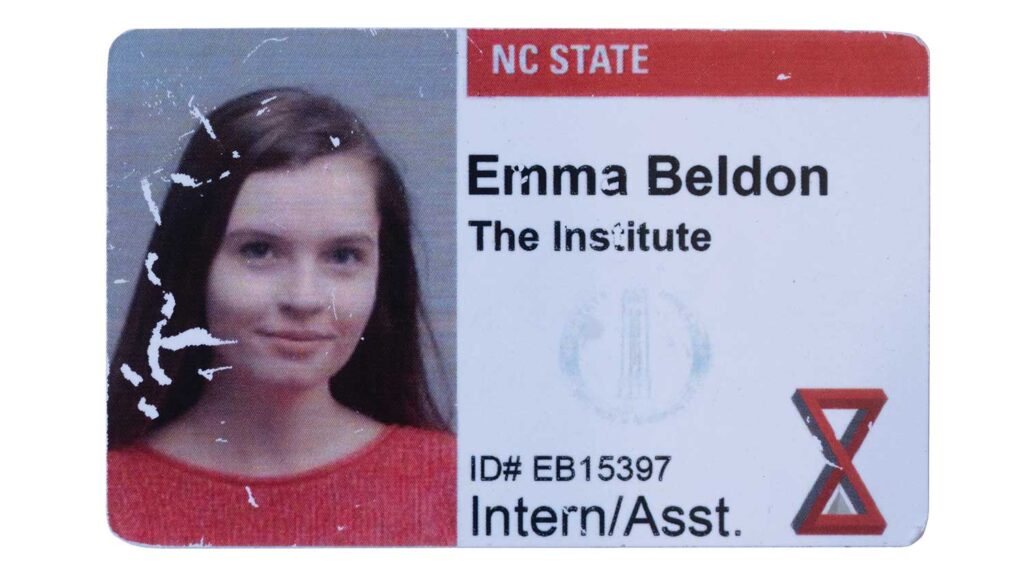

The plot was this: NC State had been secretly studying time travel at “The Institute,” housed in Broughton Hall, since the 1960s. The audience initially signed up to participate in research, but soon learned something was amiss: Three NC State students had gone missing and were presumed to be lost in time. The audience became part of a group called “the Cadre” that was trying to find the students and learn more about The Institute and Beldon, its evil founder. (And in a Back to the Future twist, one of the lost-in-time students met their parents before they were married.)

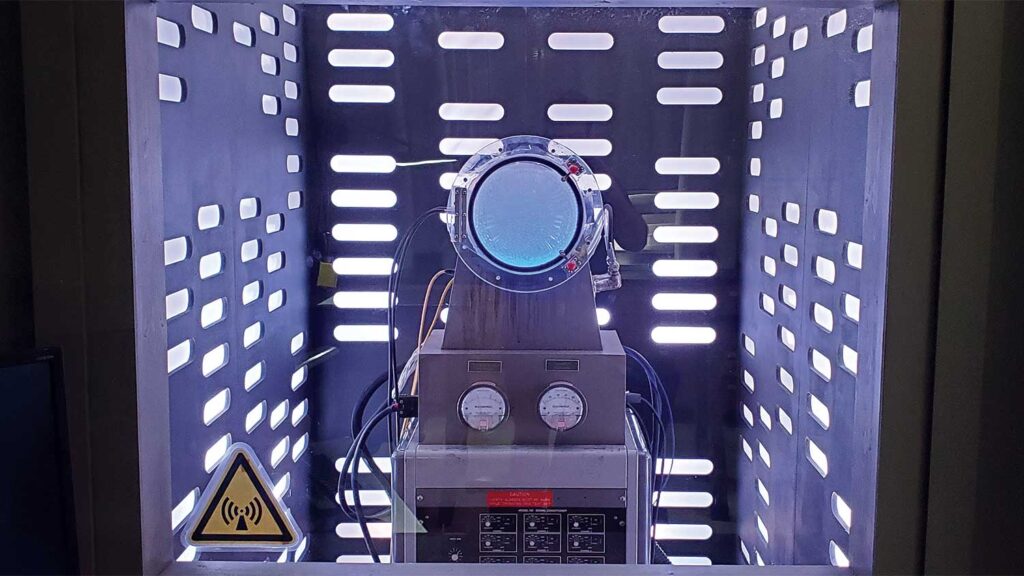

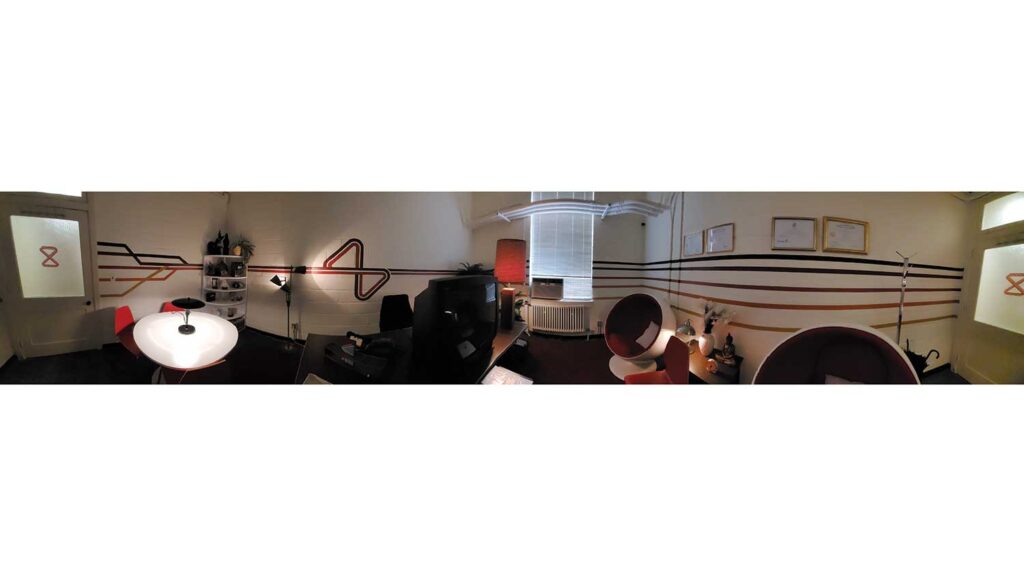

An unused third-floor lab in Broughton Hall became the recruiting office for The Institute, the first stop for the audience. Later scenes took place all over campus. A Ford F-150 pickup truck belonging to one of the missing students was parked in the Reynolds Coliseum lot in a space marked “The Institute — Enforced 24/7” with clues, such as a note with a phone number, visible on the dashboard. A third-floor room in 111 Lampe Drive was turned into a hideout where Emma, one of the students stuck in the 1970s, lived. Period details included women’s lib posters on the wall, an electric typewriter and a WKNC DJ announcing that Pink Floyd had just hit the top of the charts.

Mellema and his theater colleagues had to do a massive amount of collaboration with officials across campus. The university architect’s office helped find unused space. Campus police discussed safety protocols. University Transportation gave The Institute a parking space. The University Surplus office provided materials to build the sets. (“We told them, ‘We need all the weird scientific equipment you are about to throw out,’ ” Mellema says.) Even the University Communications office was advised — just in case anyone thought NC State was really studying time travel.

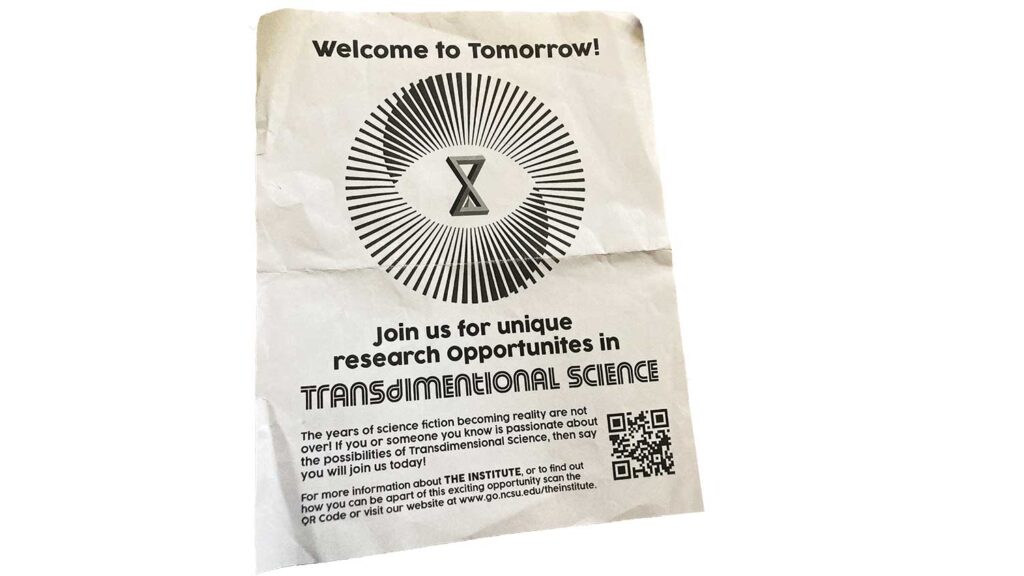

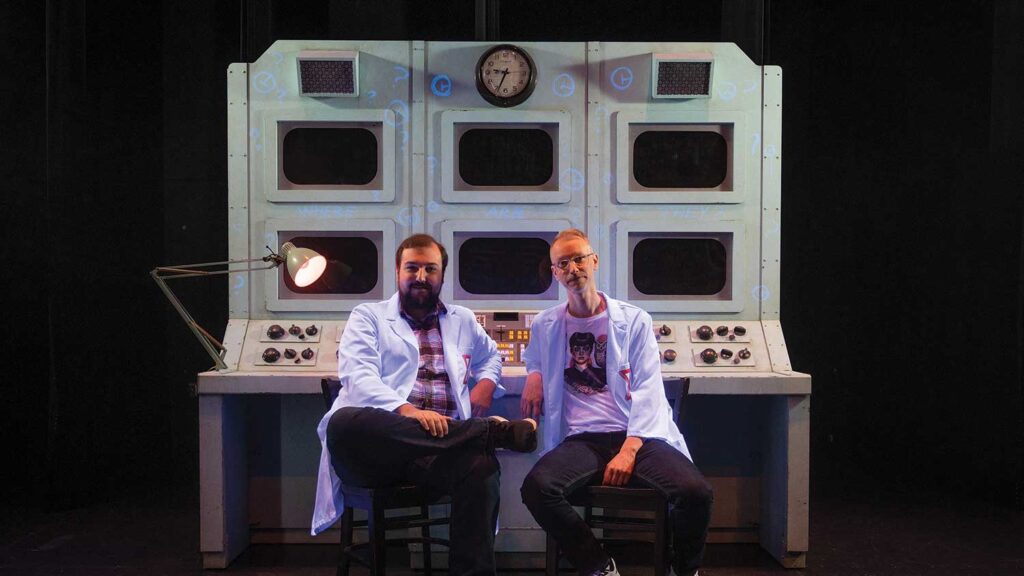

“It was logistically challenging,” Mellema says. Along with Mike White, assistant technical director, he spent the fall of 2020 and part of 2021 on all the logistics — writing scripts, building sets and scouting locations. In late 2021, the project launched with no fanfare — just nondescript flyers placed around campus. The wording was purposefully oblique: “Join us for unique research opportunities in Transdimensional Science,” it said. A QR code on the flyer led to the website.

Katherine Saul, an aerospace and mechanical engineering professor, and her husband, physics professor Matt Green, saw one of the flyers. “We love escape rooms,” she says, “and we guessed it was something like that.” They logged on and signed up. “At the first event, as we are signing forms and watching orientation videos, we started to get messages, that these people weren’t who they seemed to be and to keep our eyes open,” she says.

Every few weeks they would get an email to sign up for another session. Saul and her husband were hooked. As the story progressed, the audience learned more about the three students — Taylor, Emma and Jessica — from recorded voicemails and a journal shelved in the Hill Library stacks with its own Dewey Decimal number. “This was more than a puzzle,” Saul says. “There was an element of immersion. It was a continuing live story. We were like, ‘What’s going to happen to Jessica?’ ”

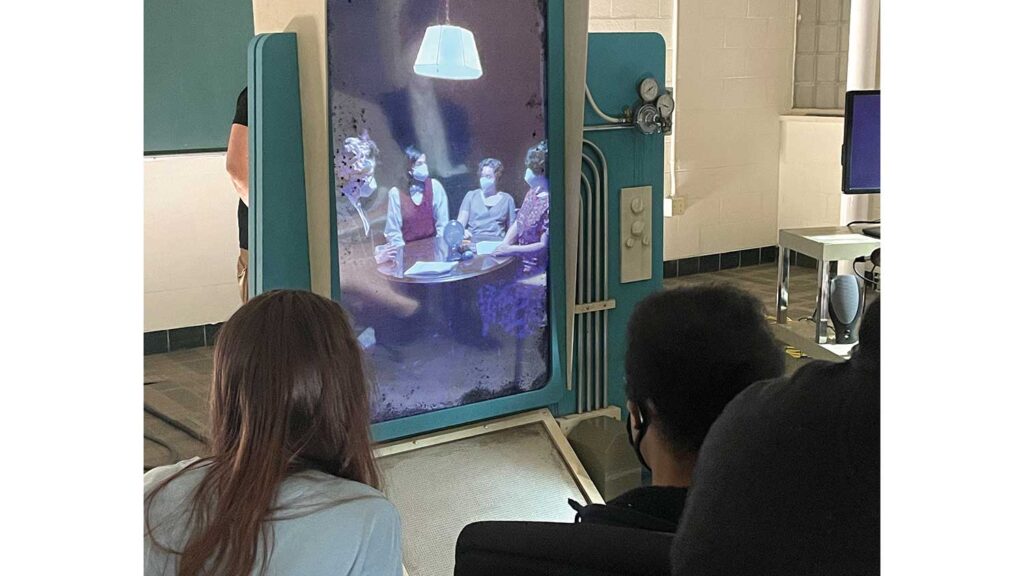

The finale came in May, several months after the quest had begun. The audience — at that point about 100 participants — gathered in Thompson Theatre where a time travel aperture that they had encountered in an earlier scene was on stage. The three missing students appeared — to thunderous applause — and, along with the actors playing other characters, held a Q&A session with the audience.

Julie Baker, an aerospace engineering major who has appeared in University Theatre productions, helped work on the script and character development in the project’s early stages. She also voiced the character of Emma, one of the missing students. But she didn’t know the entire plot or the puzzles and riddles, so she went with a friend through the entire production as a participant. “It was great to see the other side of what I’d been working on,” Baker says. She found herself in awe of the sets and the production quality. In the last scene before the finale, participants hear a disembodied, distorted AI voice. “The way it interacted with you, it felt real,” Baker says. “I mean, it genuinely creeped me out.”

“The way it interacted with you, it felt real. I mean, it genuinely creeped me out.”

–Julie Baker, aerospace engineering major and University Theatre participant

The production was designed for more than just fun. The creators wanted people on campus to develop connections with new people and create a sense of community. Another objective was to form a deeper connection to NC State and its history. For instance, participants went on a walking tour of campus where they learned that Winslow Hall was once the site of the campus infirmary, where 13 students died in the influenza pandemic of 1918.

Joshua Reaves, director of University Theatre, says the creators also wanted to engage students who would not typically go to a play. Mellema and White are both gamers who are intrigued by alternative reality games and saw parallels with the theater world.

“We wanted to engage some of those people,” Reaves says, “people who might say, ‘I’m not going to this Shakespeare thing.’ ”

That was one reason why the marketing of the program was only flyers around campus and word of mouth. “Jayme was very adamant that we not advertise it or tell people what we were doing,” Reaves says. “The narrative they created, the story itself, was built to be secretive.” A survey of participants afterward found that 90 percent had never been to a University Theatre production.

Reaves, who gave the OK to the project, says the finale gave the creators a huge sense of accomplishment. “I’ve been doing theater for a long time, and yeah, a standing ovation is great,” he says. “In this case, everyone in that audience was so engaged, so excited to be there.” Even after the Q&A session was over, he says, people stayed around to talk to the actors and the creative team — and talk with each other about their own experiences.

“We had created that community,” Reaves says.

- Categories: