The Moments of Truth

English professor Jason Miller has a knack for unveiling the hidden past to focus on the present. Photography by Marc Hall ’20 MA.

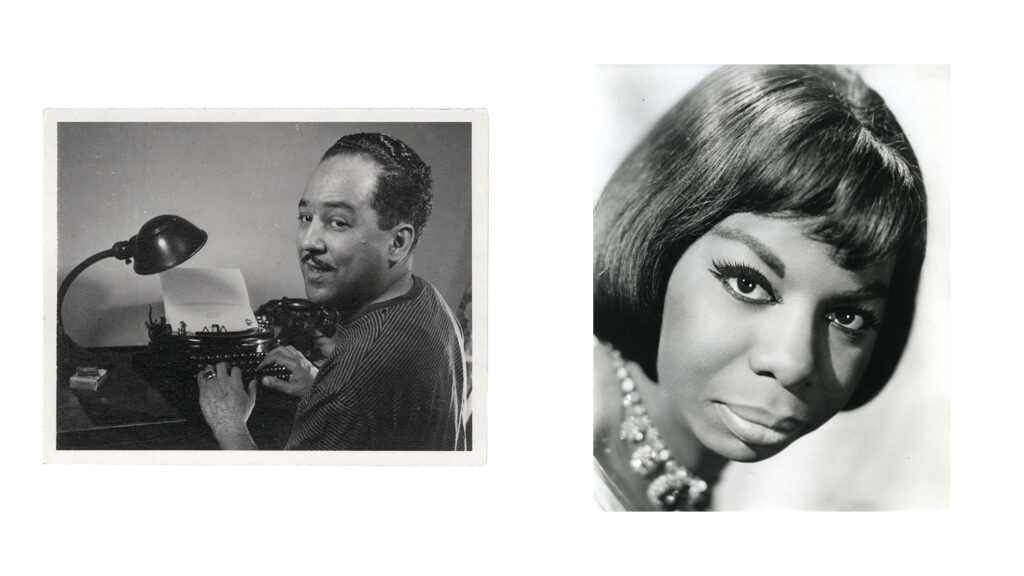

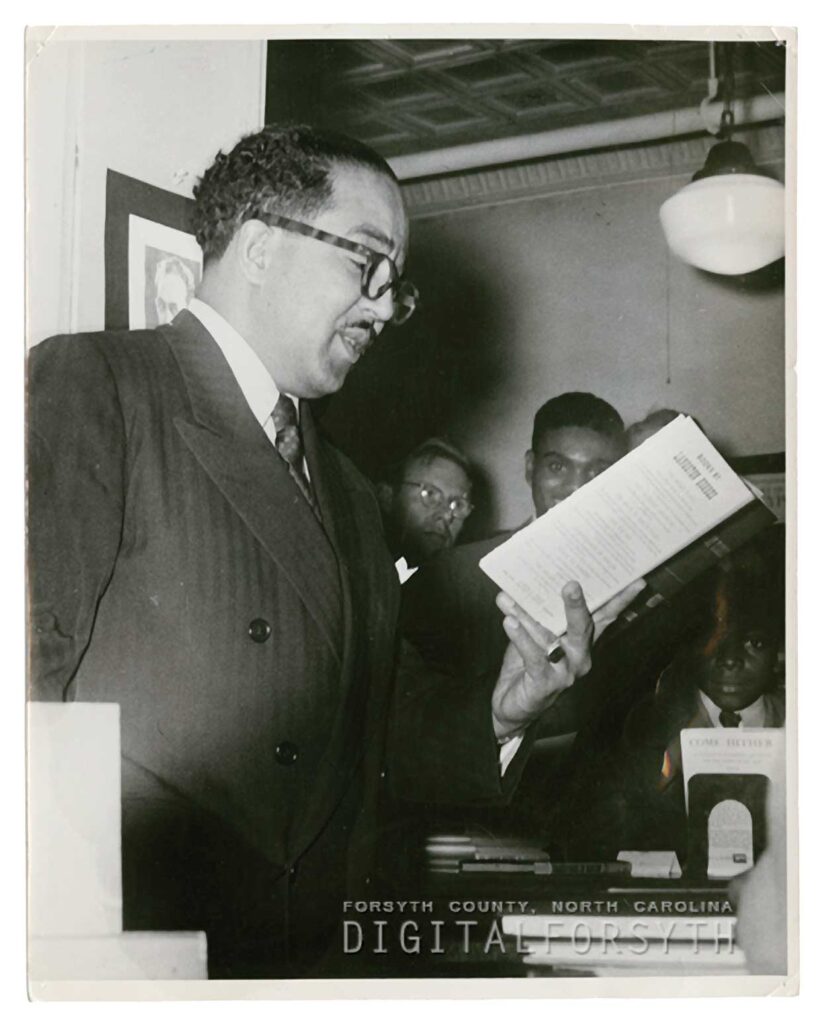

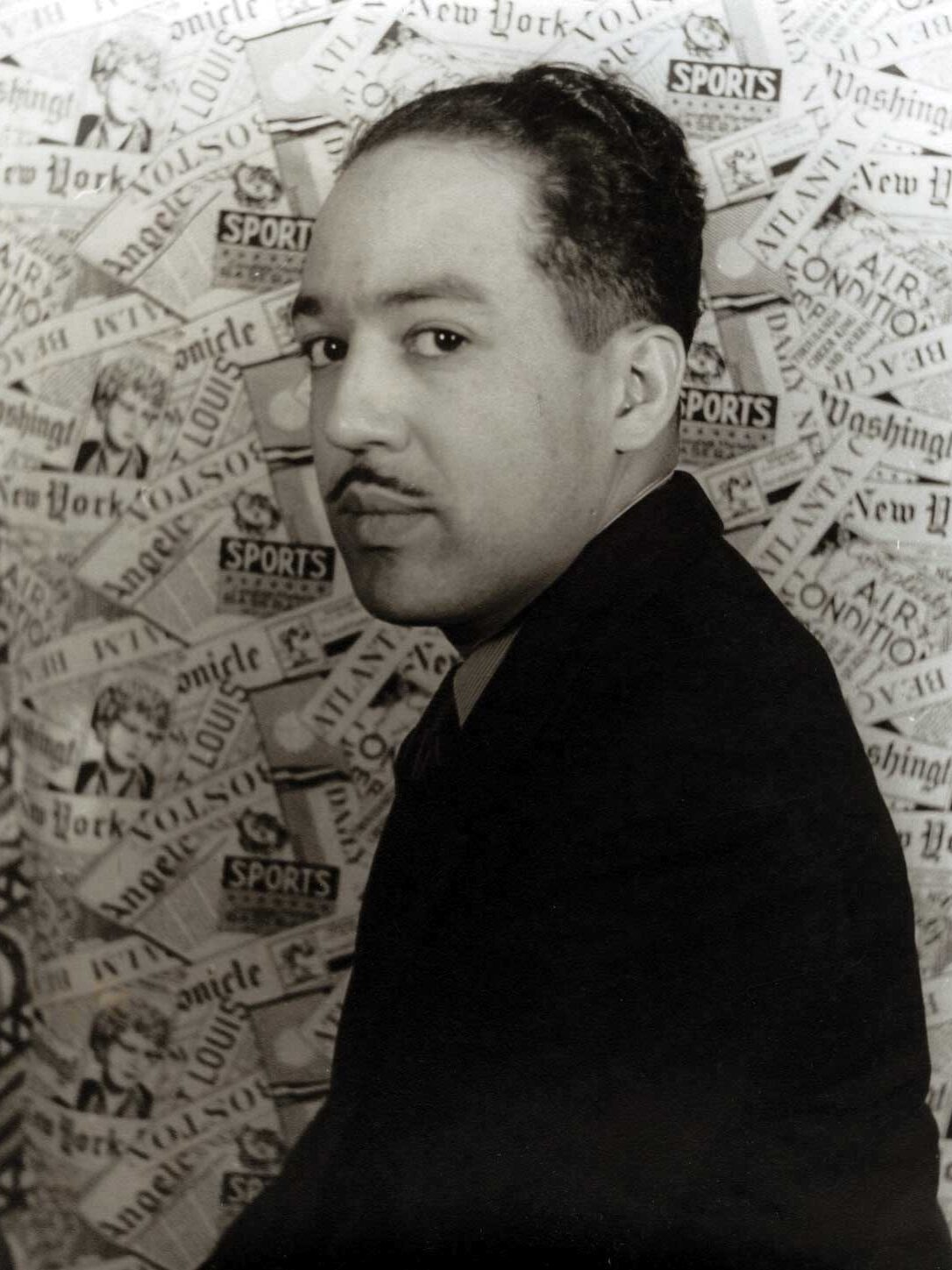

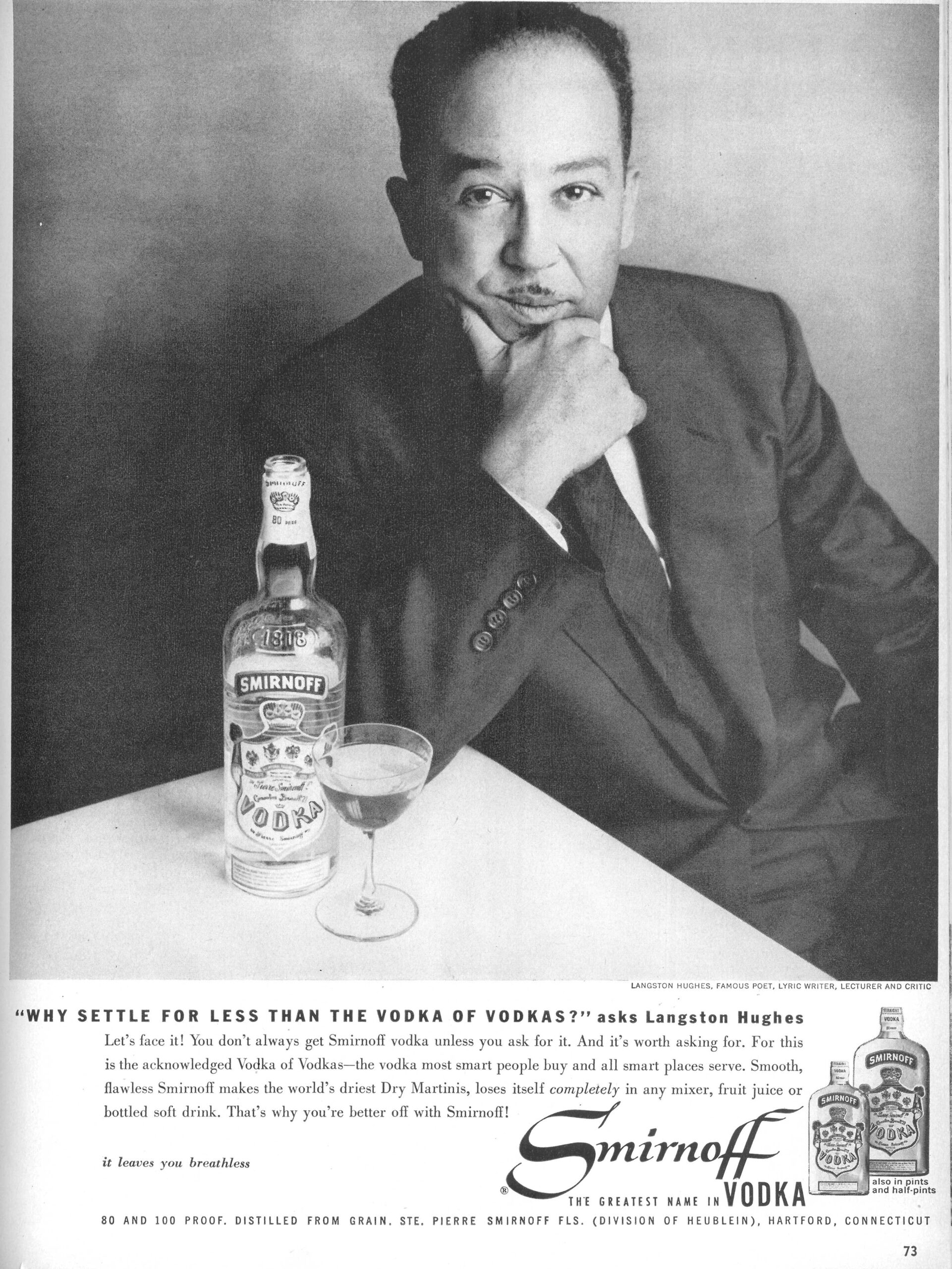

It doesn’t take long talking to NC State English professor Jason Miller to understand that for him, everything begins and ends with 20th century American poet Langston Hughes. “I was drawn to Hughes’ accessibility,” Miller says of a leader of the Harlem Renaissance movement in the 1920s and ’30s. “Here is somebody with some profound thoughts that aren’t very nuanced or so ambiguous that they’re really hard to tease out.”

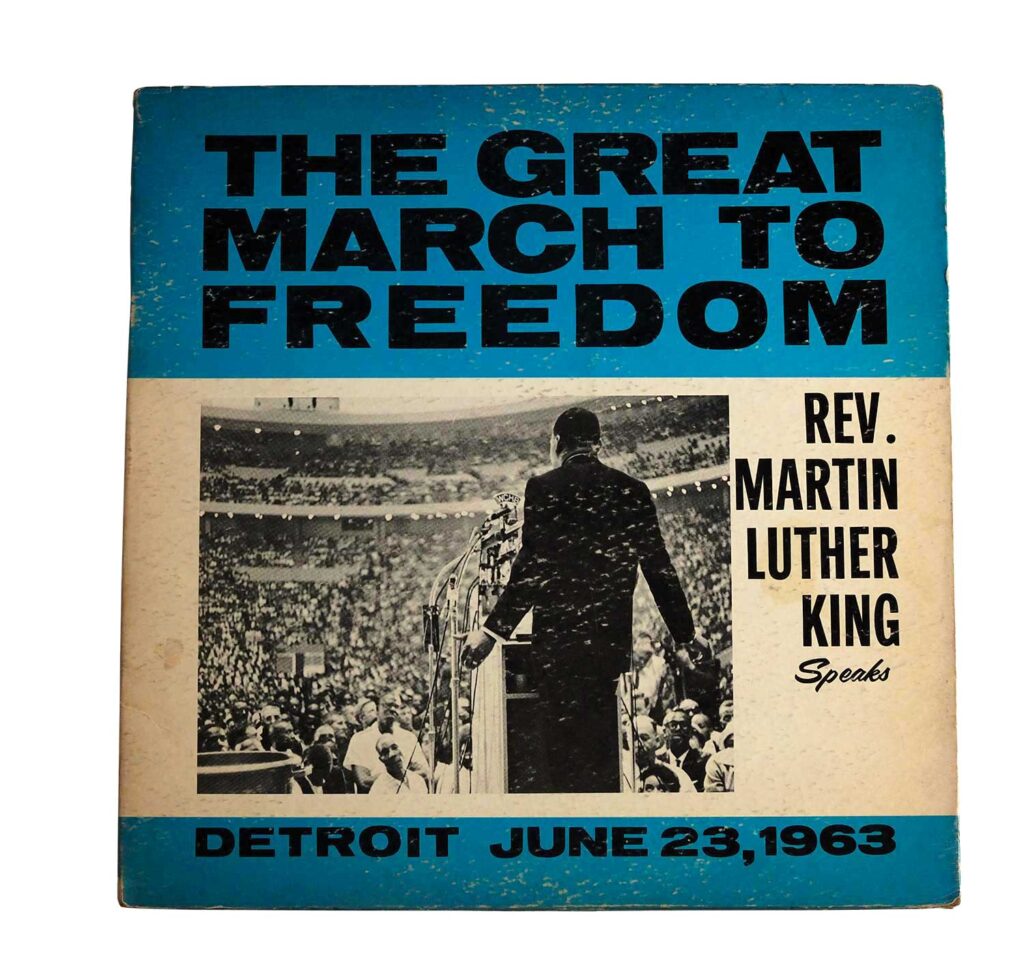

Take, for instance, one of Hughes’ most famous poems, “Harlem,” in which he asked readers to think about America’s unfulfilled promises of equality and dignity to Black people. “What happens to a dream deferred?” Hughes wrote. “Does it dry up/like a raisin in the sun?” The simplicity to that weighty question is what first attracted Miller to focus on Hughes in 2011. He wrote a book on Hughes, and then Miller continued to research Hughes’ influence on Martin Luther King Jr. And for the last six years, Miller followed where that trail led him, from King’s “I Have a Dream” speech delivered in Washington, D.C., in 1963 to how he clashed with the Ku Klux Klan in Raleigh in 1966.

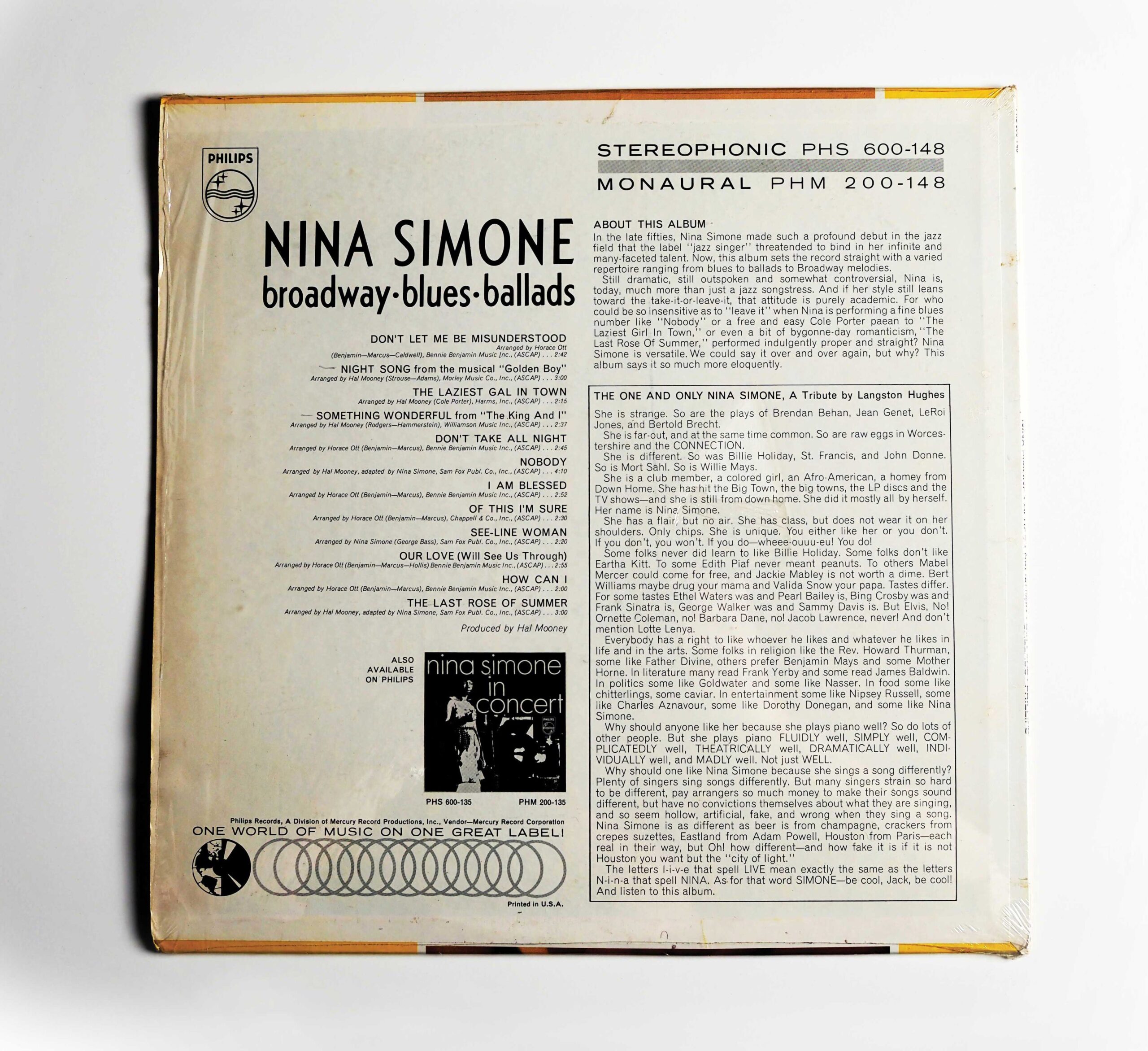

Miller’s latest project, Backlash Blues: Nina Simone and Langston Hughes, is for Miller a continuation of his research on Hughes. Featuring letters, song and poem analyses, newspaper articles and an extensive library of photos, the new online archive offers for the first time an in-depth analysis of the friendship between Hughes and blues and soul legend Nina Simone. The union was sparked by a 1949 lecture in Asheville, N.C., Hughes gave to an audience that included a teenage Simone, and their association became more intense in the 1960s. The project’s title, in fact, takes its name from a song whose lyrics Hughes wrote for Simone and gives a powerful voice to the civil rights struggle. Miller and his team of students highlight Hughes’ influence on two other hits of Simone, and argue for the first time that Hughes helped shape Simone’s transformation from shy standards singer to the High Priestess of Soul, a moniker by which she is eternally known.

The project also underscores the power of what Miller has long done with his work. Like Hughes did with his poems, Miller approaches his work with a certain accessibility. He doesn’t just write articles in an esoteric journal that only other scholars will read. Instead, he uses performances, exhibits and multimedia platforms, uncovering and bringing to life concealed histories for public consumption. He recreates moments, like King delivering the first iteration of “I Have a Dream” in Rocky Mount in 1962, nine months before the world heard it in Washington, D.C. Miller goes beyond the page and finds stories within local communities that reveal the larger essence of historical moments, some inspirational and some uncomfortable, like those in his exhibit detailing the KKK marching on Fayetteville Street and naming the men in white robes.

“This state has the first real practice of the sit-ins,” Miller says. “This state organized the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. This is a state Dr. King appears in. This is a state that birthed and shaped Nina Simone. These are North Carolina stories with North Carolina legacies. Positive and negative.

“So this is a state as much as any state in America that needs to deal with these things, understand then work through.”

Wide Eyed and Ready to Go

Miller says he’s mistaken for a history professor quite often. “And I find that wonderful in that particular way,” he says, laughing. But make no mistake, Miller, 51, is a literature scholar who has a love affair with language. Just ask him about a poet like Robert Frost. With Sunday morning evangelical intensity, Miller closes his eyes and incants, bringing to life Frost’s “Two Tramps in Mud Time.” “But yield who will to their separation/My object in living is to unite/My avocation and my vocation/As my two eyes make one in sight.”

Eyes are often on Miller’s mind. He says of his curiosity, “Our eyes will never callous.” He has adopted the epitaph of Midwestern poet Don Welch, who was also Miller’s mentor at the University of Nebraska at Kearney. It reads, “He tried to keep both eyes open.” And Miller cites the German philosopher Martin Heidegger in explaining the power of open eyes. Heidegger, Miller says, believed in the idea of “unconcealment,” that you have to be ready to see as the world reveals truths to you.

“I say it this way to my students,” Miller says. “It’s that truth really is a secret that gets repeated.”

History Hide and Seek

Jason Miller, professor in the Department of English, knows how to find the forgotten in the past. Here is a list of his projects he’s done while at NC State.

- 2011

Miller released Langston Hughes and American Lynching Culture, a book that analyzes 36 of Hughes’ works.

- 2015

Origins of the Dream: Hughes’s Poetry and King’s Rhetoric was published. Miller uncovered a reel of tape with a version of the “I Have a Dream” speech, which was recorded in Rocky Mount, N.C., November 1962, nine months before King delivered the speech in Washington, D.C.

- 2016

Miller organized Experiencing King at the Hunt Library, an immersive two-day event on King’s legacy in North Carolina.

- 2018

Miller helped put together “The Dream Is Alive,” a concert that set King’s Rocky Mount speech to music. Miller also organized and staged the reenactment of the speech in the high school gym where King originally delivered it in 1962.

- 2020

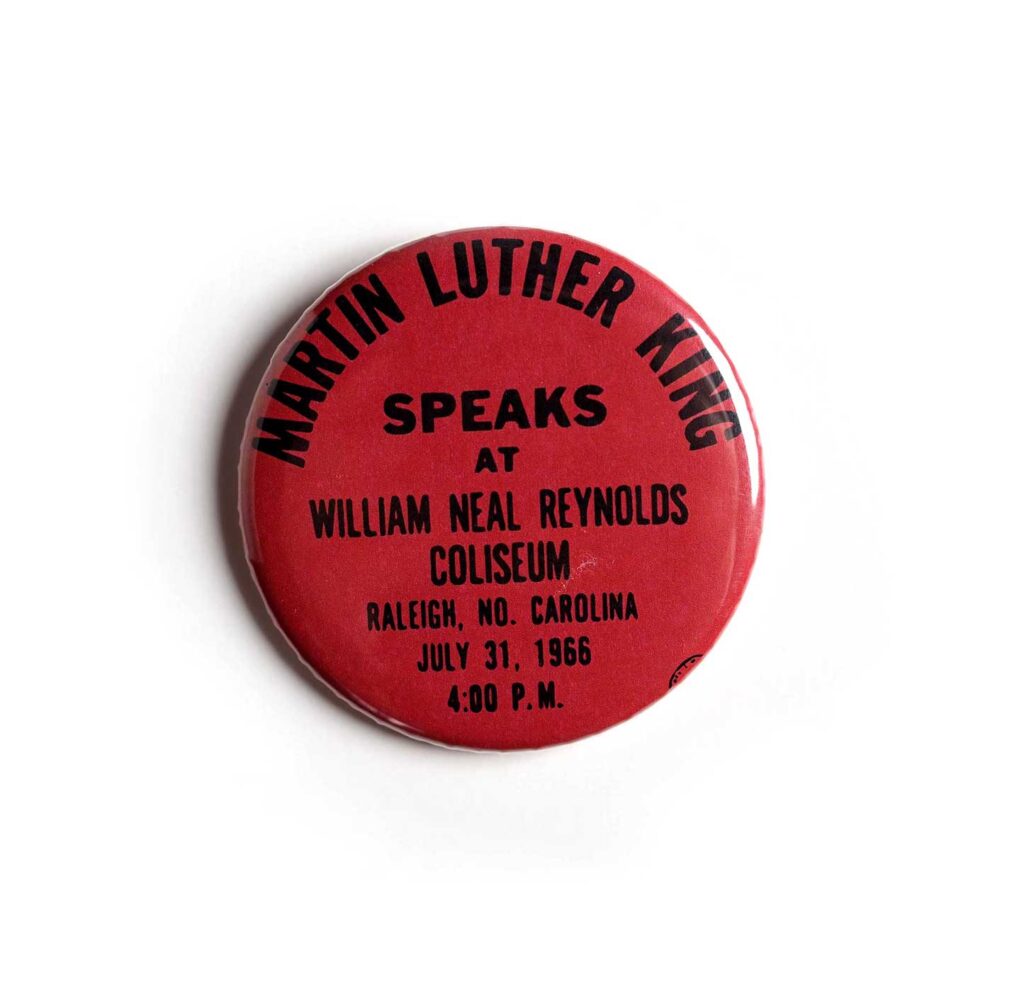

The exhibit “When MLK and the KKK Met in Raleigh” opened in NC State’s African American Cultural Center. It now is available to view in the Hunt Library’s iPearl Immersion Theater.

- 2021

In addition to unveiling Backlash Blues: Nina Simone and Langston Hughes, Miller also released Plain Sense, an online project dedicated to the life and study of his mentor at the University of Nebraska at Kearney, poet Don Welch.

Close Encounter

Miller remembers the first time he saw a secret get repeated, how truth shook him. It was 1999, and he came across Without Sanctuary, a book containing all the photographs of lynchings that had been sold or reproduced in America. Miller says he made it through only seven photographs before he had to walk away from being physically revolted. One thought stayed with him: “If I don’t know about this, I know all these other people don’t know about this.” So he then set out to identify how Hughes addressed the concept of lynching in his poetry. The result was Miller’s first book, 2011’s Langston Hughes and American Lynching Culture.

These are North Carolina stories with North Carolina legacies. Positive and negative.

When Miller finished, he had found in his research multiple instances of Martin Luther King Jr.’s use of Hughes’ words and ideas in his speeches. So came his next book, Origins of the Dream: Hughes’s Poetry and King’s Rhetoric, published in 2015. It was in that research that an extraordinary moment of unconcealment happened in 2013. Miller had traveled all over the U.S., trying to document how King had conceived of, written, drafted and edited the immortal “I Have a Dream” speech he delivered at the March on Washington, D.C., in August 1963. In a library in Rocky Mount, N.C., Miller discovered a tape reel containing an early version of the speech, which King delivered in November 1962 in Booker T. Washington High School’s gym in Rocky Mount. What sticks with him is how that discovery dispelled the myth that “faraway things are where history happens.” “I literally traveled around the country for eight years studying MLK’s ‘I Have a Dream,’” he says, “and it was an hour away, the thing I needed.”

The Dream Is Alive

One of Miller’s goals was to make sure his work had life beyond the page. So Miller launched lectures and programs in Rocky Mount in 2015. “Where the Dream Began” featured the history of King’s appearance there. He built a two-day event at the Hunt Library called “Experiencing King,” replete with walking tours, a preview of the documentary he made about King in Rocky Mount and a performance of An Evening with Martin and Langston, where actors Felix Justice and Danny Glover performed as King and Hughes, respectively. Miller went on to work with the Raleigh Civic Chamber Orchestra in 2018 to shepherd the commission of King’s Rocky Mount speech set to music by a Harlem composer, resulting in the concert “The Dream Is Alive.” That same year, he and leaders in Rocky Mount held a re-creation of King’s speech in the same high school gym where King had performed it 56 years prior.

Herbert Tillman was 17 when he was in the Booker T. Washington High School gym in 1962 to hear King speak. He remembers growing up Rocky Mount in the 1950s, not allowed to eat in restaurants with white people and only welcome in one of the city’s three white movie theaters — and that was if he sat in the balcony while the white people sat downstairs. So, he says, King’s coming to Rocky Mount was immeasurable in what it meant to Black people like himself. “Just because he was from Georgia didn’t mean he didn’t know about what was going on everywhere. It was happening here in Rocky Mount,” Tillman says. “Those were times we really needed for someone who could give us inspiration.”

For five-plus decades, Tillman says, the memory of King’s appearance stayed alive in Rocky Mount’s Black community. But elsewhere, he says, there was little recognition of it around town. That is until Miller started showing up asking to interview people who attended King’s appearance in 1962 and when he discovered the tape of King’s speech. Tillman says it was emotional to hear the speech played again and that it immediately took him back to being in the gym, a moment that he and other Black citizens in Rocky Mount had long held on to. “And now [Miller] has opened this jar and has made it known,” Tillman says. “And making it known does validate you. It’s one of those things that make you feel good.”

Miller then further dove into King’s impact on North Carolina. Eighteen-hundred members of the Ku Klux Klan marched down Fayetteville Street in Raleigh on a July day in 1966 to counter King’s appearance in Reynolds Coliseum. Miller turned his research about the day into an exhibit and a series of lectures titled, “When MLK and the KKK Met in Raleigh.”

Working on his research during a residency at NC State’s African American Cultural Center, Miller found more than 150 photographs of the march in the State Archives, providing an up-close lens into virulent racism. Men dressed in white robes. Children by their side. Counter-protestors meeting the Klan. Miller also interviewed eyewitnesses to that day in 1966. And he found some historical records, such as KKK newspapers that were circulating with pictures of King and an advertisement in The News & Observer by Raleigh churches that labeled King a communist. “[Miller] made Raleigh a living heartbeat in all of this as MLK and the KKK were living blood cells passing through it,” says Austin Horne ’20 MA, a former student of Miller’s who researched the 1960 Newport Jazz Festival for the project.

It’s the work after the moments are revealed that Miller finds indispensable. “I’m not only gathering materials,” he says, “but then by doing it publicly, more people come forward.” In Rocky Mount, someone in the community told him the code — in case people were listening in on the phone — for visitors to come to the house where King was having dinner in 1962: “The blueberry pie is ready.” A woman told Miller that her father took her to Fayetteville Street on that day in 1966, telling Miller, “My daddy said, ‘Come here. I’m going to show you what hate looks like.’”

“You’re literally looking eye to eye with somebody who experienced it,” says Miller. “And you’re going, ‘This is a community tale.’”

Facing the Backlash

In early 1949, Hughes was traveling through North Carolina set to read his poetry at a series of events celebrating what was known as “Negro History Week.” One of these events took place in Asheville, where he spoke at the Allen School, a private institute. It was there that one of the most influential American poets of the 20th century spoke in front of a young lady in the audience who would grow up and become one of the most revered American singers of the 20th century: Nina Simone.

Miller’s Backlash Blues: Nina Simone and Langston Hughes pinpoints the moment as the genesis of a long friendship between songstress and poet. And it’s just one of the many treasures visitors can uncover on the project’s website, along with pictures from the 1960 Newport Jazz Festival featuring Hughes alongside blues legends Muddy Waters and John Lee Hooker, a review of Simone that Hughes wrote in the Chicago Defender at the outset of her career, and original Christmas cards Hughes and Simone sent one another.

The beginnings of the project stretch back to just before the pandemic hit in 2020. Miller was giving a talk about a Hughes biography he’d written. He mentioned to the Raleigh audience that he had come across some research suggesting Hughes had an intense and lifelong friendship with Simone, who is from Tryon, N.C. People in the audience wanted to know more. “It was right there in front of me,” Miller says. “And it was continuous in every way.”

So, Miller and his students in his graduate class on Hughes set about unconcealing. They studied liner notes from half a dozen albums. Miller interviewed Simone’s most noted biographer. They virtually dove into Hughes’ papers at Yale University. Miller, who serves as managing editor of Backlash Blues, gave his students the idea to research a different strand of the pair’s relationship, turning the work over to them. Students worked during spring 2020 and found their own moments to unseal. Kelli Pryor ’21 MA found a YouTube video that showed Simone sitting in the audience of a Muddy Waters performance at the 1960 Newport Jazz Festival, where Hughes held sessions educating people on blues music. Isaac Hughes Green ’21 MFA tracked every performance of “Backlash Blues” by Simone and annotated all the variations of lyrics. Lauren McKenzie ’21 MA connected with a writer in western North Carolina and compiled enough resources to map out every day of Hughes’ weeklong 1949 visit in North Carolina.

McKenzie says that when talking to Mary Burnette, a former western North Carolina resident, about her recollections of hearing Hughes talk that year, Burnette told her, “If we don’t tell our stories, they die with us.” “Yes, this is a huge project,” McKenzie says, “but it’s one small thing that connects us.”

And the key to that connection is Miller’s commitment to looking back, something he sees as the only way to propel us forward.

“These notions of what’s happened to lynched bodies, how Dr. King was treated, how Nina Simone’s been overlooked, they’re things that I recognize as absolutely born from domestic terrorism and white supremacy,” says Miller. “It absolutely has relevance to our daily living.

“The easiest way to say it is, anything unacknowledged is a thing that is unknown and unrepaired. You’ve got to acknowledge something before you can repair it. And whatever degree that takes and requires is quite unique.”

- Categories:

So important.

So well documented.

So proud of Dr. Jason Miller.

So proud of NC State !!!