Here’s To Harrelson 1962 – 2016

In 2016, we looked at Harrelson Hall's legacy at NC State. Love it or loathe it, it left quite an impression on campus.

By Josh Shaffer

For more than 50 years, Harrelson Hall has loomed over the Brickyard like a flying saucer on stilts — a circular freak of a building that flummoxed students with its spiral ramps, windowless classrooms and ductwork that whooshed like a subway tunnel.

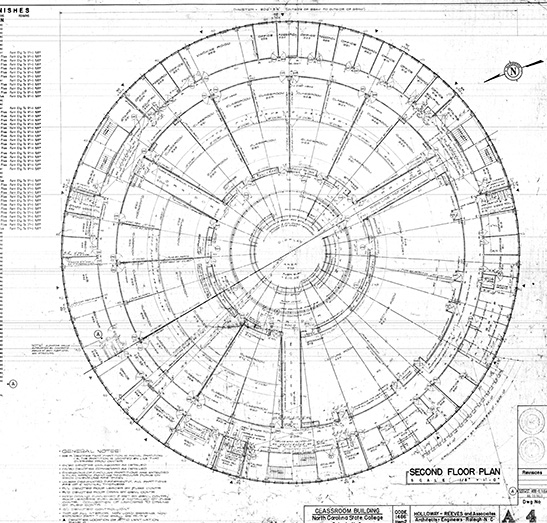

It spawned horror stories from students who wandered lost inside its cork-screw hallways, craned their necks to see equations scribbled around curving blackboards and struggled to make sense of restroom stalls shaped like pie slices.

It inspired ridicule and pranks as much as scholarship.

Four agricultural engineering students drove an MG Midget up the ramp in the late 1970s. Skateboarding in Harrelson became an unofficial sport at NC State, as did roller-blading, shopping cart riding and Super Ball bouncing. (A video posted on YouTube — just search for “Harrelson Hall” — captured 2,000 balls bouncing down the ramp.)

But Harrelson’s long reign as NC State’s best-known oddity has expired, and the demolition date is drawing near. As the campus says goodbye to this misfit of a building, a curious fondness is emerging for the structure, which will be reduced to a heap of rubble this summer.

Its construction did, after all, grow out of a burst of 1960s energy, a period of daring that launched the space program and urged a crew-cut-wearing nation to grow its hair into a Beatles mop. Harrelson’s designers believed architecture played a vital role in shaping and improving human life, giving it zest and originality. For all their mistakes, those minds earn posthumous marks for effort.

To understand Harrelson, it’s important to remember how the campus looked prior to 1962, when the building opened its doors to students. In that era of conformity, much of NC State looked like a place that spared every expense on its buildings, churning out rows of bland brick boxes and leaving the fancy stuff to Chapel Hill.

And today, a few still offer a tribute to Harrelson and the inventive spirit it tried to represent. “That building was about the future,” says Marvin Malecha, dean of the College of Design from 1994 to 2015. “It was about trying new things.”

Indeed, no ordinary university building could bear the name of John William Harrelson ’09, the first alumnus to serve as NC State’s chief administrator.

An overachieving and no-nonsense scholar, Harrelson worked his way through college by ironing his classmates’ clothing (for 12 cents an hour) and dimming the campus lights each night at 11 p.m. He rose to senior class president, head of the Mechanical Society, business manager of the Agromeck and captain of the student military squad before graduating in 1909. He served in both world wars. Students knew him, affectionately or not, as “Colonel.”

His namesake building rose at a time when the university, much like the nation, was staring into a grand future. Enrollment in the early 1960s stood at 6,000, a total that was expected to nearly triple by 1975. NC State needed a building to handle this growth: not just the numbers, but the increasingly complex educational world created by a society that was hurtling quickly into television and computers.

Enter E.W. “Terry” Waugh, a professor recruited to the design school by Dean Henry Kamphoefner.

Born in South Africa, educated in England and Scotland, Waugh loathed the style of architecture then dominating the American South, which he derided as stale imitations of old Charleston, Williamsburg and New Orleans. In his book, The South Builds, he dismissed the landscape of buildings around him as a “charade” and “a mockery of the vigorousness of our forefathers.”

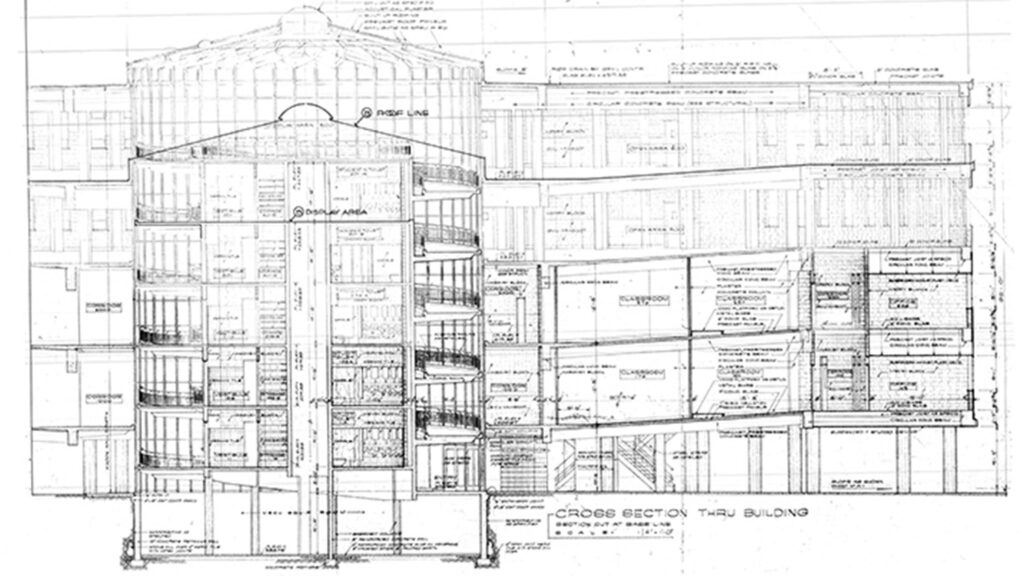

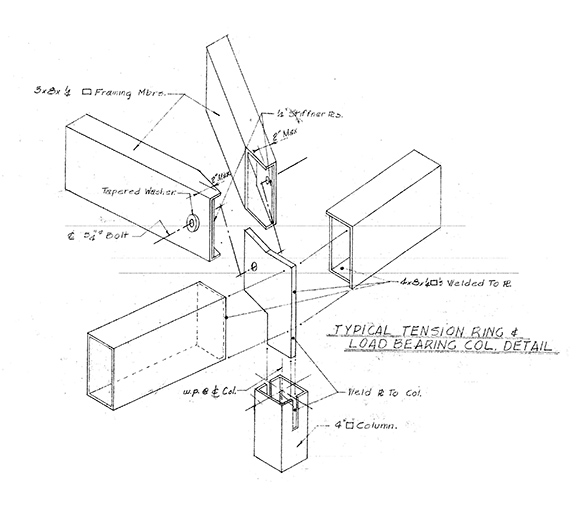

Waugh called for a new approach to fit a new world. He spoke of carrying torches and meeting human needs. For him, buildings could and should inspire the young minds bubbling inside of them. Showing off his drawings of Harrelson, he described a “spiral ramp floating around an inner vertical cylinder,” hardly guessing his creation would one day host shopping cart races.

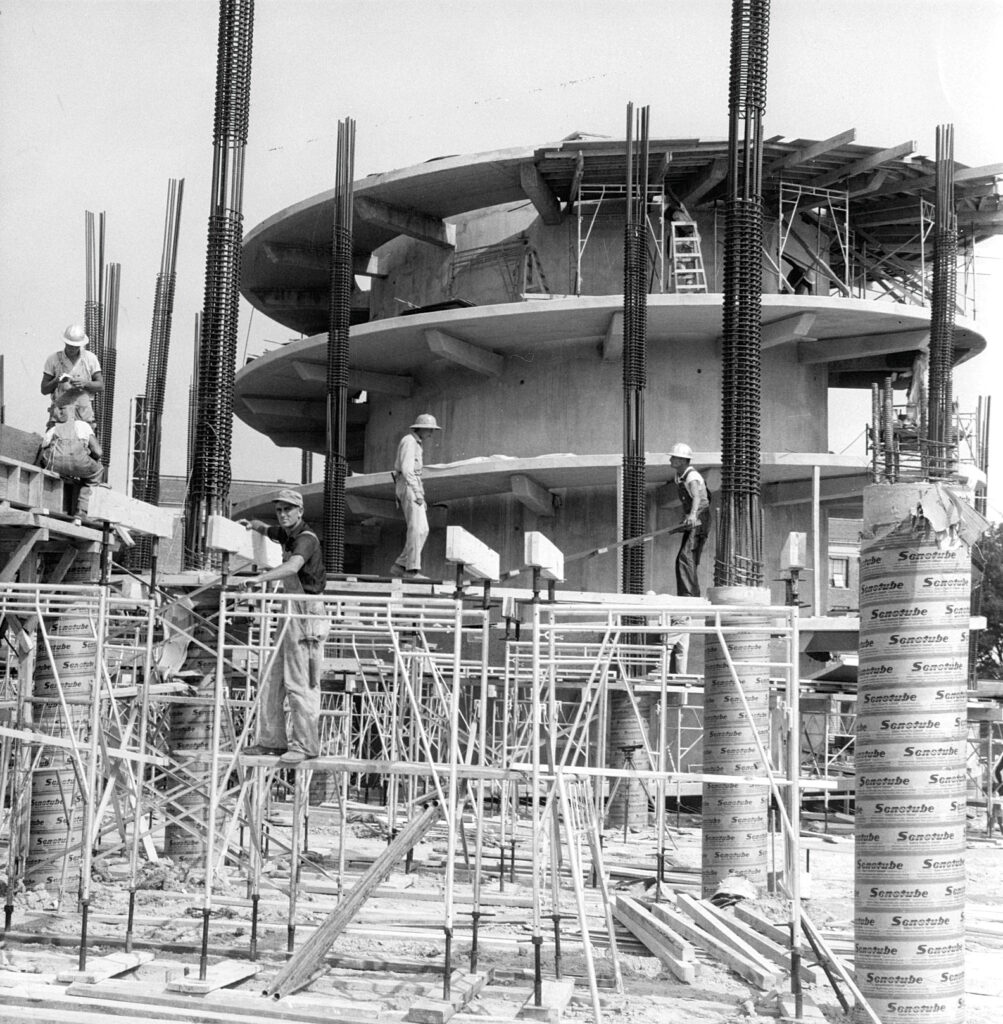

What emerged in 1962, at a cost of $2 million, was the first-ever cylindrical building on a college campus. The News & Observer carried its picture on opening day, calling it “magnificent.” The Dispatch, in Lexington, N.C., reported, “State College students . . . are now becoming acquainted with one of the most unusual buildings on an American campus, or in the world for that matter,” adding that “from a distance it looks like a great white cake.”

At the time of Harrelson’s debut, Ted Halverson ’64, of Gaithersburg, Md., was working toward his nuclear engineering degree. He recalls everything else about campus, and the world at that time, being uniform and rectangular. Suddenly a building with curves appeared on his treks across campus, offering fresh scenery.

“It was fascinating to watch it grow,” says Halverson, a retired engineer. “Everything just sort of went up like an ice cream cone.”

“It was fascinating to watch it grow. Everything just sort of went up like an ice cream cone”

—Ted Halverson ’64

Then came the puzzled head-scratching from passing students. It looked like an air filter or a stack of soup plates. “You heard stories about maybe it was a spaceship,” says Jerry Johnson ‘67, of Cocoa Beach, Fla., who is retired from the Air Force.

Once students got inside, the novelty quickly faded.

In his math class, Halverson couldn’t see all of the notes written on the curving blackboard — a privilege afforded to lucky students whose last names started with the right letters in the alphabetical seating chart. “I had to rely on one of my classmates’ notes,” Halverson says. “I think I got a ‘C.’” (The blackboards were later reconstructed to lose their curves.)

Hatred of the new building grew quickly, spawning a slew of campus legends, all of them false. Some students believed that Harrelson was slowly sinking into the ground. Another story offered the theory that Harrelson had been a senior project turned in for a failing grade, and that the student who dreamed it up had managed to get it built out of sheer revenge.

As the years passed, so grew Harrelson’s reputation as NC State’s boondoggle — a tag that will follow it to demolition. By 1972, the first nail was put in its coffin when an annual report from the Department of History called it “one of the most unsatisfactory academic buildings imaginable.”

The list of complaints spanning decades could fill a thesis, and the disorienting, curlicue hallways would form exhibit A. A few years back, during a brief stint inside Harrelson, Mark Tulbert would often see the same student circling past his office three or four times within a few-minute span. From his vantage point, Tulbert, who helps oversee the campus’ performing arts series, saw helpless wandering as the shared plight of students. “If they deviated from their path at all,” he says, “they got lost.”

Harrelson had stairs on the outside of the building, forcing climbs in 90-degree heat or freezing cold. The air-conditioning system could not keep up with the building’s demands and classrooms were often hot and stuffy. The chairs all sat fixed to the floor. And the bathrooms? They formed the nucleus of the building’s shell, all of the stalls rotating around the center point like wedges in a Trivial Pursuit game piece.

Raleigh writer Carrie Knowles foolishly tried to use these facilities in roughly 1990, when her husband taught sociology in Harrelson and she was pregnant with their son. When she attempted to exit the stall, great with child, she got trapped by Waugh’s attempt at trying new things.

“The only way I could get out was to stand on the toilet. The door kept bumping my stomach. There was no way to get out of the stall with this giant baby.”

In its defense, with decades of hindsight as a crutch, Malecha notes that Harrelson Hall may have been a victim of budget-slashing. Maybe, had the building been designed the way Waugh wanted it, Harrelson might have lived up to its round potential.

But maybe not.

Maybe it demonstrates the chasm between ideas on sketch paper and reality in poured concrete, a gulf between its designers’ dreams and the demands of practicality. Malecha says he hates to second-guess Harrelson’s creators and offer a critique from half a century away. But, still, he says, its designers might have added windows in key places, giving its users some sense of direction while they navigated its innards.

“They became,” he says of the designers, “too much a slave to geometry.”

But on its way to oblivion, we can offer Harrelson some thanks for trying, for starting a conversation, for refusing to be dull.

But on its way to oblivion, we can offer Harrelson some thanks for trying, for starting a conversation, for refusing to be dull. Harrelson veteran (both as a student and English professor) Wanda Ramm ’96, ’99 MA has two farewell wishes for the round building. “I would like to ride my bicycle from the top to the bottom,” she says. “And I would like to push the button.”

Sorry, Wanda. There is no button. Even in death, Harrelson won’t be giving anyone the satisfaction of watching it implode. Too many vibration-sensitive facilities (chemistry labs, a nuclear reactor) nearby. Instead, the building will be taken down piece by piece and hauled away, its concrete core crushed to be reused in road beds. Some of the limestone panels will live on—at least temporarily—in the form of benches that will grace a landscaped spot on the circular site.

But eventually they’ll be gone, too. Plans call for a new classroom building at the south end of the Brickyard. And, yes, it will have corners.

- Categories:

As a 1974 graduate of the School of Design (now College of Design), I had two math classes in Harrelson. Loving contemporary architecture, Harrelson was a fun building. I have fond memories of walking through the Brickyard and glancing at Harrelson. Thank you for this terrific article!

I am not of course free of bias here, as I am Terry Waugh’s daughter. Nonetheless, as a former art historian (graduate school at BU and UNC-CH), I have read many reviews of art and architecture.

This article stands alone as one that insults the architect and the times. You ridicule the building endlessly while not investigating its strengths at all, and its place in history. Very disappointing.